Japan, the Kingdom of Characters

by Florian

There’s almost no way to interact with anything Japanese without running into cute, fictional characters of all kinds. What may look childish at first sight is one of Japan’s major sources of cultural influence and a sizeable industry of its own, built on licensing rights and merchandise.

コンテンツ

Origins of the character business

The Japanese character business has its roots in the post-WW2 era, starting in the 60s. Unsurprisingly, this coincides with the rise of anime. In the first 10-15 after the war, people were mainly focused on the necessities of everyday life. The main concerns were finding a place to live, getting stable jobs, home appliances, cars, and so on.

The first big breakthrough was made by Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy, debuting as a TV series in 1963. From this point onward, more and more anime were made, and more and more characters with them. Some of the oldest Japanese media franchises that are still alive today have their origins in the late 60s: Doraemon, Sazae-san, and GeGeGe no Kitaro, for example.

The life of the average person in Japan changed drastically between 1960 and 1970. At the beginning of the seventies, the Japanese economy had more or less recovered from the effects of the war and entered a phase of stable growth. By the early 80s, the quality of life of the average Japanese citizen had reached the international standard.

With all their basic needs covered, people increasingly started looking for ways to individualize. This kind of development is hardly unique, but in Japan, it went hand in hand with the spread of Kawaii Culture, and eventually, even adults grew fond of characters that were once considered to be “for kids”.

While Japanese characters were always popular, it’s impossible to talk about characters and IPs as a business without mentioning Disney. Disneyland Tokyo opened in April 1983, and the resonance was overwhelming. Only one year later, 10 million people had already visited the park. The way Disney marketed its characters hugely influenced how Japanese companies handled theirs. This mirrored the effects American animation had on the Japanese animation industry a few decades earlier.

Current situation

In 2019, the size of the Japanese character industry was 24.2 billion USD, a slight increase compared to the previous year. The biggest single category was toys, which made up almost 50% of all revenue. The rest was made up of products from smaller categories – food, sweets, stationery, clothing, and so on. These categories were highly varied, none of them exceeding a share of 10% on its own.

Characters and character goods have spread throughout Japanese society. While new ones are popping up constantly, there are also a lot of old franchises that have grown up with their original target audience, the current parent and grandparent generation. Many IPs have gone on from targeting just children to targeting families, and a wider variety of people is buying merchandise. Even in Japan, you won’t see an office lady sporting a Hello Kitty t-shirt on a regular workday, but smaller goods like key chains, pens, or small figurines are widely bought and used by adults as well.

In everyday life, characters can be encountered where you’d never expect them … at construction sites, for example.

Source: The Tokyo Times (https://www.tokyotimes.com/construction-barrier-animals/)

Different media, different characters

It’s easy to get lost in the sea of Japanese characters. However, they’re not all the same. How they are marketed and how people interact with them is heavily influenced by their origins. Let’s have a look at the different types of media that Japanese characters come from.

Manga and Anime

This category is, without a doubt, the first that comes to mind. Manga and anime are arguably Japan’s biggest cultural exports, but even then, getting all the way to the top can be hard.

The reason lies in the source material. Anime and manga are narrative media with plotlines, and most of them end eventually – which in turn gives their characters a certain shelf life (excluding the mega-hits, of course). Compared to the other categories, characters origination from anime or manga also have a rather complex production and marketing process that involves lots of different actors like the source material creators, animation studios, toy makers, TV stations, etc.

With restrictions like these, one winning strategy is to create a show where characters just don’t age, and a larger overarching plot is non-existent. Examples here are Anpanman, Sazae-san, and Doraemon. Merchandise and other products from this category tend to target a very young audience.

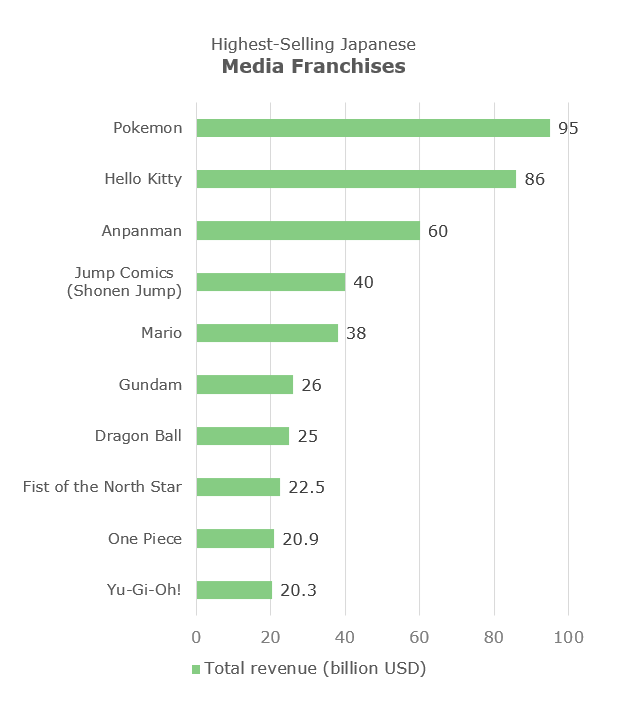

However, there are also a few series with proper (and extremely drawn-out) stories that have managed to rack up respectable numbers. Right now, the biggest franchise built on a single, ongoing story is One Piece, with a cumulated revenue of around 21 billion USD. Other big hitters are classics like Dragon Ball, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Fist of the North Star, Naruto, and KochiKame (the latter being not so well known outside of Japan).

Games

The current holder of the title “highest-grossing media franchise” (worldwide!) comes from the game category: Pokemon. The franchise sits at the top with a whopping total revenue of 95 billion USD, and with new games still coming out, there seems to be no end in sight.

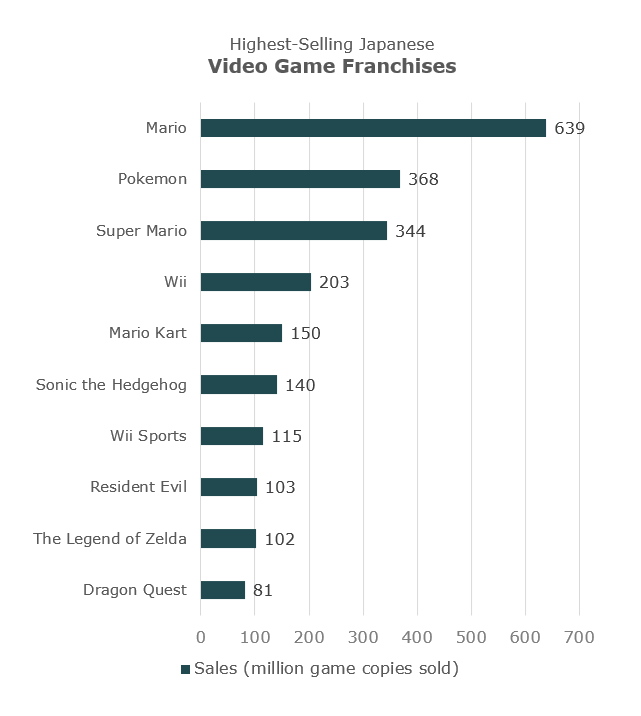

Next on the list is Mario, with 36 billion. But when focusing only on the games, Mario outperforms Pokemon. This shows just how much money Pokemon makes from licensed merchandise – over three times as much as from the video games! This selling power clearly comes from its multitude of characters. The designs are both simple and appealing enough to be turned into all sorts of merch.

Sources:

List of highest-grossing media franchises

List of best-selling video game franchises

You could argue that characters play a bigger role in Japanese video games compared to those from the west, where there tends to be a bigger focus on gameplay and graphics. This kind of “soft power” is especially prevalent in Nintendo games. The company’s hardware is consistently behind the competition, but Nintendo makes up for the lack of appeal on the tech side by drawing on beloved and creative IPs.

But even then, new game franchises have to match certain standards if their characters are to gain any popularity. Similar to anime and manga, the success in the “home medium” comes first, and large-scale merchandising only becomes a concern when a certain degree of popularity has been reached.

Mascots

“Mascot” is a convenient umbrella term describing standalone characters. But looking more closely, you can divide them into two sub-groups. On the one hand, you have “business”-type characters that were created purely for merchandising purposes, like Hello Kitty or Gudetama (both by Sanrio).

On the other hand, there are “true mascots” that, while also created with merchandise in mind, serve a double role as representatives of companies or communities. Mascots of cities, prefectures and other municipalities (ゆるキャラ) are especially famous. In terms of popularity, the mascot of Kumamoto prefecture, Kumamon, has been dominating the polls for years.

From a business standpoint, characters from this category might be the most sustainable. Their appeal is rooted solely in their design, free from the pesky bonds of plots and game mechanics. Especially when they’re created by in-house artists and designers, marketing schemes involving them can be drafted up much faster and easier. In fact, a flexible licensing system played a huge role in the growth of the Hello Kitty franchise.

What’s interesting about mascots from a creative as well as a business perspective is that their greatest strength also poses a very high hurdle for creators and marketers to overcome. Anime, manga, games, and TV shows can “hook” people with a range of different things. However, mascots are bound to fail if their design or personality doesn’t grab people’s attention.

This is probably one of the main reasons why many Japanese mascot characters are so notoriously quirky. The need to be recognized in any kind of way gives birth to creatures like Melon Kuma, a terrifying cross between bear and melon from Yubari City in Hokkaido … and many others. If a daily dose of weird mascots is what you need, check out the Twitter account Mondo Mascots.

Source: Melon Kuma Offical Twitter Account (https://twitter.com/melonkuma2019/status/1136936900231516160)

The future of the character business

Cute characters have gained society-wide acceptance in Japan, and it’s unlikely that their prevalence (as well as the size of the markets attached to them) will sharply drop in the foreseeable future. However, it’s also true that a lot of them are still made with kids in mind. With fewer and fewer children being born, Japan’s population decrease will affect the way characters are made and marketed in the future.

At the same time, the related industries are internationalizing. Historically, most Japanese companies mainly targeted a strong domestic market. But in the past few decades, things have started to change. The anime and manga industry, for example, has seen a huge increase in revenue from overseas licensing, and the most popular franchises like Pokemon or Hello Kitty all operate on a global scale.

It’s safe to assume that this trend will continue, opening doors to foreigners. So keep your eyes peeled – who knows, maybe one day you’ll be working for the company who created your childhood heroes!

Recommended Posts

May Sickness: A Japanese Phenomenon

10 5月 2021 - Daily Life, Life